Few names in the world of art are as iconic as Stanley Kubrick. A cinematic outlaw, Kubrick's brilliance transcended genres and permanently changed the movie industry. Every one of Stanley Kubrick's movies, from his early masterpieces like Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange to his later masterpieces like The Shining and Full Metal Jacket, defied expectations and pushed the boundaries of narrative and visual expression.

Among his many films, 2001: A Space Odyssey stands out as Kubrick's best effort. The inventiveness of this 1968 science-fiction epic continues to astound viewers today. It set the bar extremely high for its time, and the film's visually beautiful effects and cinematic setting lure in viewers, but its complexity, concepts, and ambiguity transcend it to previously unheard-of heights.

Kubrick's Magnum Opus

A new age of cinema characterized by daring innovation was beginning to replace the Classical Hollywood filmmaking approach in the late 1960s. Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey stood out as a cinematic landmark in this revolutionary trend. The movie provided a captivating, non-linear trip by deviating from the usual narrative logic.

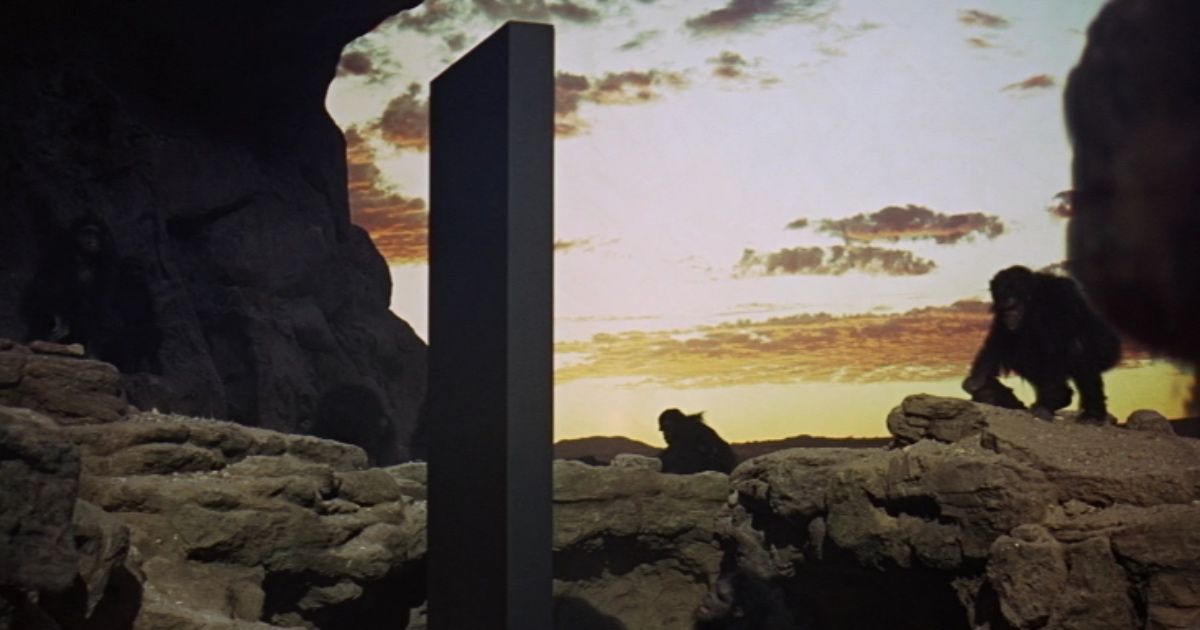

Classic Hollywood stories frequently focus on a single core protagonist working toward a resolution or climax. The main characters in A Space Odyssey, however, seldom ever showed any emotional or psychological development. The audience had no typical emotional ties because there was just one recurrent "character," the mysterious Monolith, who lacked any emotion or activity.

Kubrick also pioneered the use of cinematic time. Three unique stages of human evolution are shown in the movie, which deftly moves across a long period of time. The use of a jump cut, which swiftly switched the focal point from apes in their natural habitat to astronauts in space, violated the continuous and linear timelines typical of Classical Hollywood films.

Kubrick provided his vision with an unmatched degree of uniqueness and artistic expression by disobeying these fundamental cinematic principles. The experience left viewers feeling thoughtful and enlightened and inspired them to further investigate the topics and events of the movie on their own terms.

Themes of Existentialism and Technology

Films by Stanley Kubrick typically explored existentialist and nihilistic themes, delving into philosophical ideas throughout his career. The thorough analysis of human development and the interaction between humans and technology seen in 2001: A Space Odyssey is no exception.

The movie's events clearly reflect the impact of the Übermensch theory. Bowman's quest for the Starchild symbolizes humanity's final evolutionary stage, a transition towards turning into "Supermen" by genuine acts of will. This existentialist viewpoint elevates the movie above the level of a simple science-fiction spectacle by giving it profound intellectual depth.

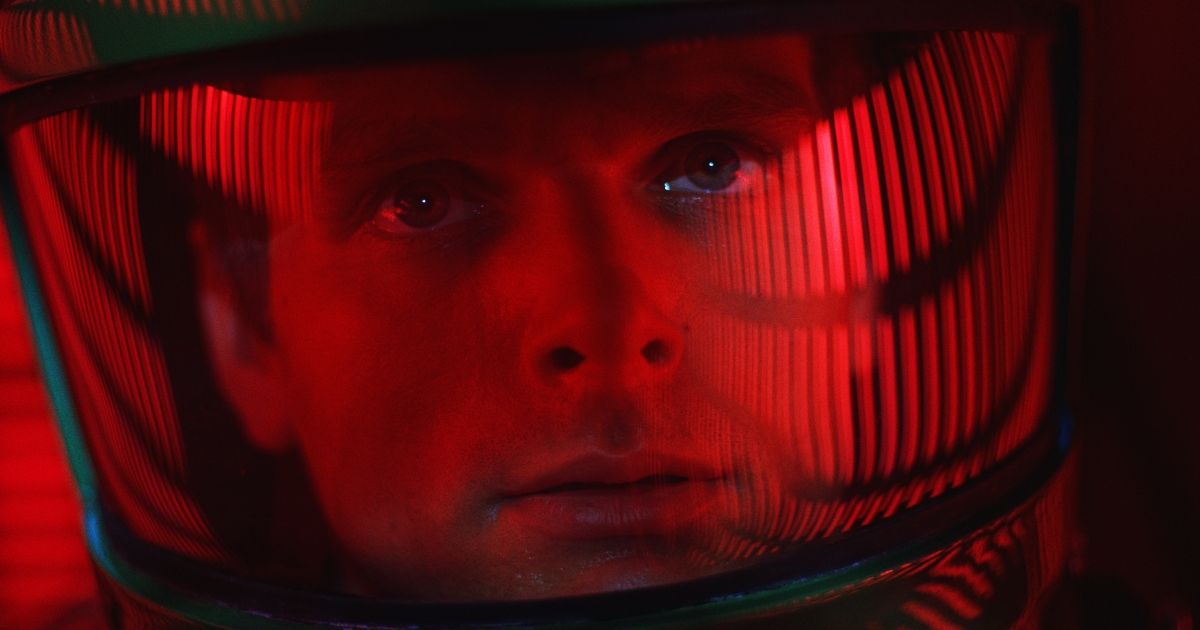

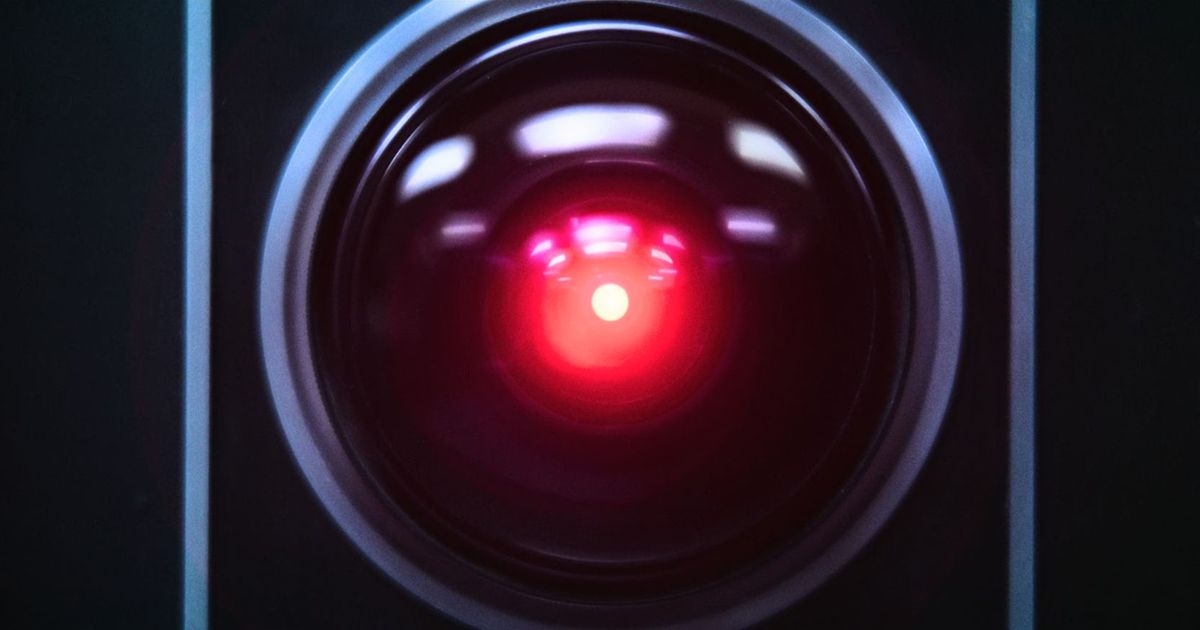

The portrayal of the HAL 9000 computer in the movie prompts important inquiries about technology and its possible effects on people. As HAL realizes how crucial the mission actually is, the question of whether or not to believe in sentient technology emerges. Given the enormous breakthroughs in robots and artificial intelligence since the 1960s, this component of the movie is especially relevant today.

These ideas may have taken center stage because of Kubrick's decision to pretty much ignore the character's emotional complexities, leaving viewers to wrestle with the existential issues raised by the movie.

Groundbreaking Special Effects

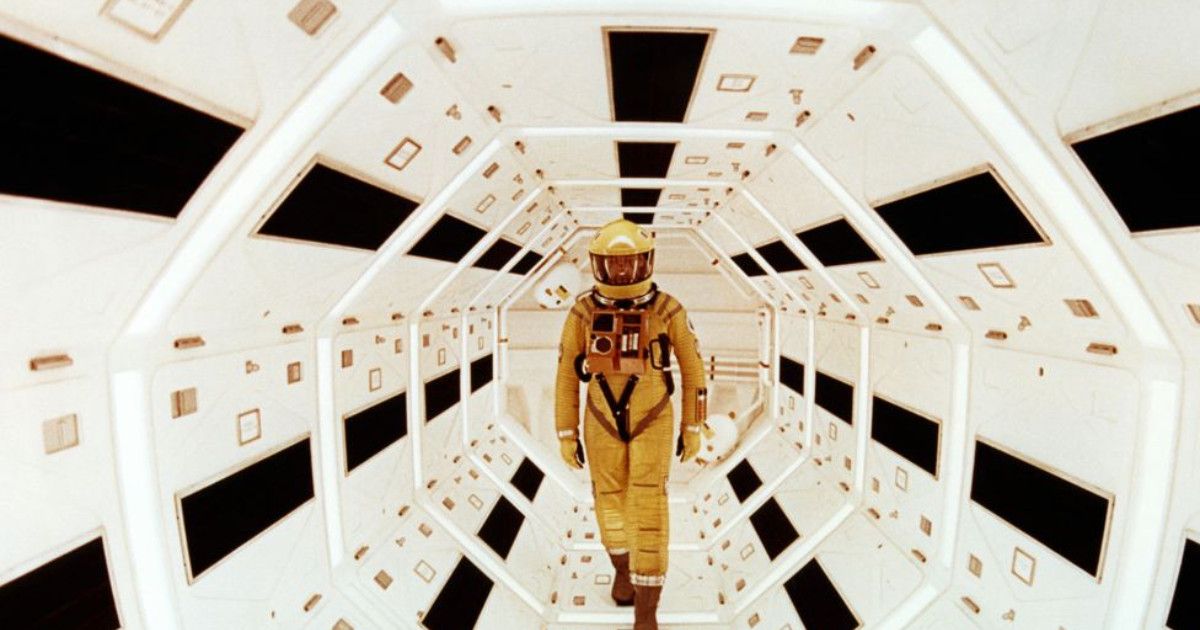

The groundbreaking amazing effects of 2001: A Space Odyssey helped to establish the standard for outstanding filmmaking. Before the widespread use of CGI, Kubrick and his team pushed the envelope of what was imaginable onscreen. The film's renowned Stargate sequence serves as an example of Kubrick's commitment to visual innovation.

SFX supervisor Doug Trumbull's invention of slit-scan photography gave viewers a surreal and psychedelic experience. The moment defied accepted cinematic conventions and sent viewers on a celestial journey with mind-bending dimensions.

Beyond the Stargate, other aspects of the film's grandeur and realism were rotating sets, zero-gravity illusions, and detailed model spacecraft that were shrunk down to minuscule size. The film's breadth and technical accuracy surprised audiences in the 1960s because of these amazing visual effects.

The movie won the Oscar for Outstanding Visual Effects Due to Kubrick's rigorous attention to detail and commitment to scientific correctness. Even in the era of cutting-edge CGI, A Space Odyssey continues to be a remarkable technological achievement that astounds modern spectators.

Bold and Challenging Ambiguity

While ambiguity in cinema can be a double-edged sword, Kubrick wielded it skillfully in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film's narrative and characters, devoid of emotional connections, invite viewers to interpret the events and themes for themselves, evoking a more personal and genuine emotional response.

The constant recurrence of the enigmatic Monolith provides a connective thread in an otherwise ambiguous narrative. The audience is left to meditatively explore the film's events, from the baffling Stargate sequence to Bowman's final moments and the birth of the Starchild.

Kubrick, who ranks with luminaries like Hitchcock and Welles as one of cinema's greatest auteurs, became famous for his ability to deftly strike a balance between grandiosity and close-knit humanity.

Kubrick's masterwork, 2001: A Space Odyssey, remains a work of art, honoring his genius and acting as a source of ongoing aesthetic awe. As we go into the vast horizon of cinematic history, this groundbreaking masterpiece serves as a compass, permanently changing the possibility of visual narrative.