Adding spark to this summer’s Oppenheimer buzz is director Steve James’ intriguing new documentary, A Compassionate Spy. The filmmaker, whose previous work includes masterpieces like Hoop Dreams and The Interrupters, weaves together a captivating tale in his latest movie, which transports audiences back into the heart of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s Manhattan Project, singling out the youngest physicist on the Manhattan Project, Ted Hall, the spirited leftist who decided to pass key information about the bomb’s construction to the Soviet Union. The layered documentary also reveals how Hall and his wife, Joan, kept that big secret throughout their 52-year marriage.

That’s just one of the things that make A Compassionate Spy a worthy investment. It also offers another look at the 1940s, Oppenheimer’s impact, and the genesis of the Cold War. Steve James, always an expert storyteller, also employs several creative concepts here that give this documentary a distinctly unique feel. It is also generous at how it doesn’t quite Hall to be a villain. Rather, James presents a young man who was conflicted about the ramifications of Oppenheimer’s lethal weapon. This isn’t an explosive story in any way, and some may argue it could have been trimmed 15 minutes or given a broader platform to explore even more.

Either way, A Compassionate Spy is one of those rare docs that effectively captures the mood of an era — in this case, the 1940s — and the men who ultimately changed the course of history.

Tick, Tick, Boom

It’s curious that some 80 years after Oppenheimer began gathering his crew of scientists and physicists in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to work on the atomic bomb, we find ourselves sitting in the summer of 2023, pondering two films that shed new light on the era. Oppenheimer, starring Cillian Murphy and Robert Downey Jr., has garnered nearly $500 million to date, becoming one of the higher-grossing films of 2023. What’s left out perhaps is a deeper look at some of the other players involved, and that’s where Steve James’s doc comes in.

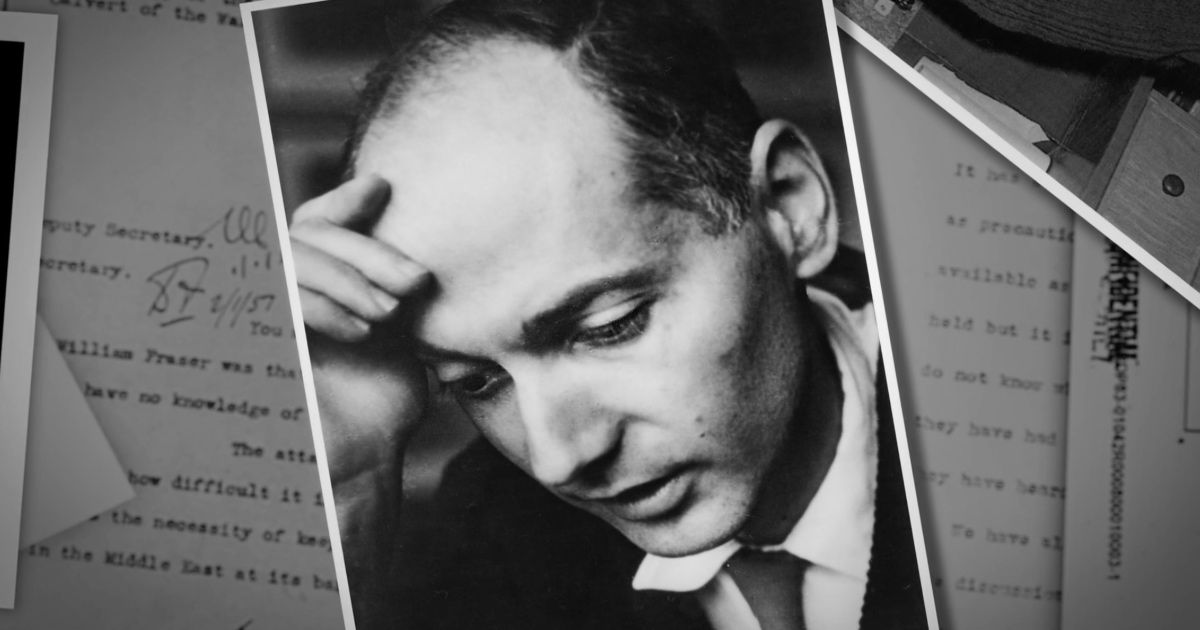

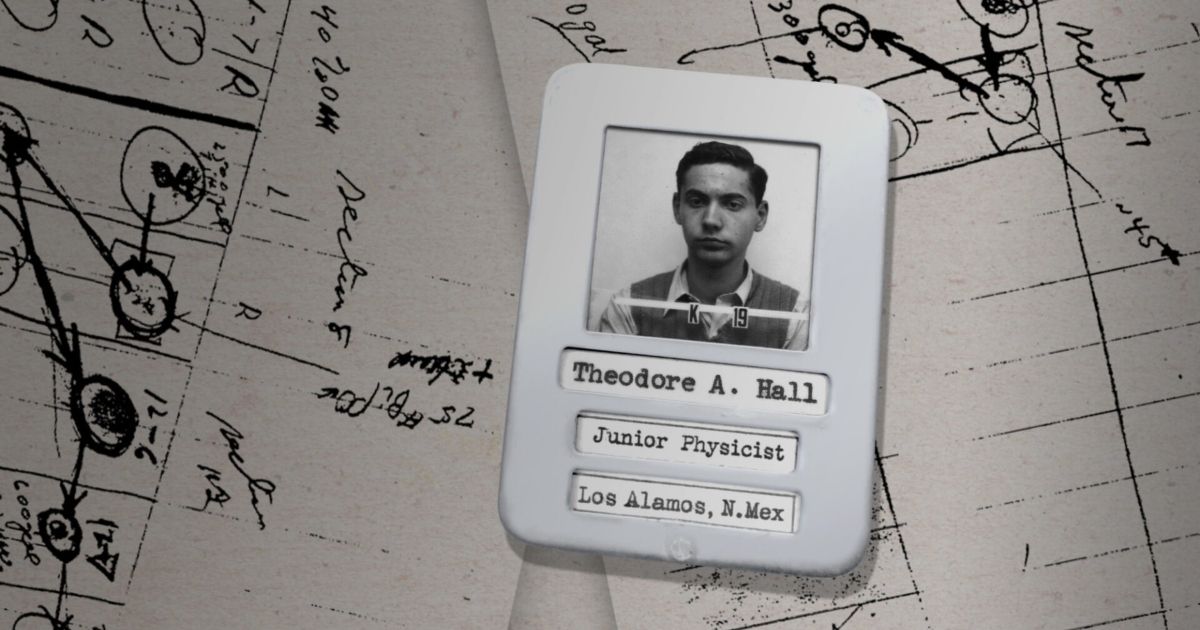

A Compassionate Spy uses a combination of vintage photographs, recreations, and various interviews with noteworthy talking heads, James captures Ted Hall’s story in fair and revealing light. We learn that Hall, at just 18 years old and a senior at Harvard, dove into the Manhattan Project. He’d become the youngest physicist on the endeavor, in fact, and, perhaps the most reserved, often seen as quiet yet politically expressive. When the other Los Alamos scientists let loose during after-hours parties, Hall could always be found in his own quarters, contemplating his time there, or listening to music.

That’s because something kept pecking away at him from inside. Hall never fully backed a future that found the United States being the sole holder of atomic bombs. How would that play out if one power on Earth held all the power? This interesting fact gives James plenty to work off of, and you can see how much research went into creating this tale.

A side note: James knew nothing about Hall, or much of the subject going in. Imagine his surprise. That sense of wonder and intrigue shows up on screen, particularly when the filmmaker, seemingly fascinated by all the facts, expertly hands his audience one significant bit of information at the time — Hall deciding to share secrets with Russia being the main blow. Understanding why Hall did that, and therefore understanding the man, is a major focus here, but James takes care to reveal the ripple effects of Hall’s actions, in his own life and with others around him.

The Ripple Effects of One Man’s Actions

Prior to August 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hall was concerned that with Germany losing the war, a U.S. post-war monopoly on a powerful weapon like the atomic bomb, would lead to nuclear disaster. James shows us the motives behind Hall’s decision to pass along key information about the bomb to the Soviets, beginning in the 1944. But he doesn’t simply give audiences a typical spy story. There’s much more here.

Enter Joan, Hall’s wife. The director manages to deliver an incredible love story in A Compassionate Spy. We learn that Joan was a key figure Hall’s life and, perhaps, sanity. She convinced him to keep his secret throughout their marriage. The couple’s children didn’t know about Hall’s actions, either. All the while, countless FBI scrutiny ensued for many decades. In Oppenheimer, audiences see the man being grilled by government officials in a lengthy process. For Hall, it was more covert. There was never a time to really breathe and settle in.

While actors recreate many scenes throughout A Compassionate Spy, there is a point where we learn from Joan that in the early 1950s, she and Hall collected everything in their home that could possibly tie Hall to the Communist Party and the couple proceeded to toss their findings in the Chicago Drainage Canal in the dark of night. Another sobering realization — at least for viewers — may be Hall’s own admission, offered from a 1988 recording Joan made in their Cambridge home: “In my mind this was a question of protecting the Soviet people as well as our people… preventing an overall nuclear Holocaust which affects the entire world.”

Hall passed away 10 years later, in 1998, but his voice and intentions are captured effectively here. We may officially be in the dog days of summer, where such heavy matters seem too deep to deal with. But it would be a loss not to. And with Oppenheimer already giving audiences plenty to think about, it’s refreshing to see Steve James offer another look at the times, and a man, like it or not, who just wanted to do the right thing.

A Compassionate Spy, from Magnolia Pictures, hits theaters and VOD on Aug. 4.