Oppenheimer is one of Hollywood’s biggest and most anticipated releases of the summer and the year. The story is an uncompromising dissection of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life as a public figure. His story is one of joy, horror, and tragedy involving the Atomic Bomb’s creation. It is a story much more than a standard biography of Oppenheimer’s life.

Instead, it is a film that shows the horrors of what this Bombs creation did to him and those around him. Director Christopher Nolan wisely splits the movie into covering the three distinct chapters of his life. With it being his highest-rated film on Rotten Tomatoes, it makes one wonder why it’s so good. Oppenheimer succeeds by being something other than a standard biopic.

Oppenheimer’s narrative does not start with the obvious beginning. Instead of simply starting with his childhood, the film begins with his time at Cavendish Laboratory. The story follows this intellectual upbringing, then goes into his time on the Trinity Project and the Bomb’s creation. The final chapter follows the aftermath of its detonation and the repercussions Oppenheimer himself faced. Each piece is a distinct portion of his life, but the film tells it incredibly inventively.

Nolan Plays With Expectations in the First Half

The film’s marketing shows two very distinct narrative choices. Certain sequences are in color, while others are in black and white. Both perspectives are inter-spliced throughout the first half. Oppenheimer’s first hour focuses on his early life, primarily covering his time at Cavendish University. This includes more of his interpersonal relationships outside the scientific world. These moments allow actors like Florence Pugh to shine.

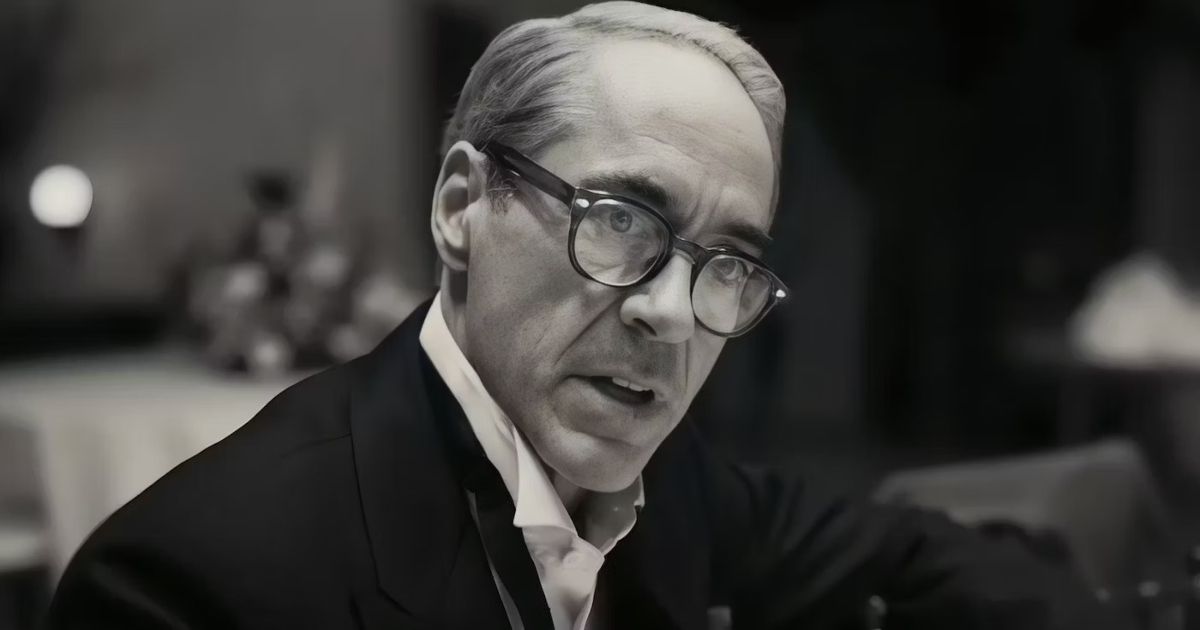

His time with Jean Tatlock (Pugh) is arguably some of the most romantic in the film. Their tumultuous relationship was continuously filled with banter. In the movie, both characters meet at a communist rally (even though Oppenheimer was never a communist). Both Pugh and Murphy portray the characters as being intensely loyal to one another. That loyalty makes the eventual demise of Jean feel all the more tragic. This time with Jean is intercut with black and white sequences of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) taking place after the creation of the bomb.

While this article is breaking down the ending, It is essential to have this information. The second half and ending of Oppenheimer become a very different kind of movie. Throughout the first half, Strauss has been perceived as a colleague of “Oppy” (as his close friends call him). His growing paranoia and eventual hatred of him come as a shock to viewers.

This reveal takes one kind of scientific horror film and turns it into more of a paranoid thriller akin to the movie of the 1940s. Oppenheimer’s shift in “horror” tones begins with the introduction of William L. Borden (David Dasmalchian).

Allegiances Shift for Oppenheimer

Christopher Nolan has warned that Oppenheimer is “kind of a horror film.” When Oppenheimer finds that Strauss has lied to him, it unlocks another horror. He realizes that his lifelong “friends” can no longer be trusted. The sequences of Oppenheimer and his friends in the AEC (Atomic Energy Commission) hearings show an unfair fight.

They keep information “classified” from Oppenheimer, making this a losing battle for his legal defense. Over time, he loses his credibility, which is detrimental to his mental health. The ability to become a “destroyer of worlds” makes him deal with the repercussions on a psychological level.

Taking a strain on his personal and professional life, “Oppy” starts to run out of friends. A brief meeting with President Truman (A campy but effective Gary Oldman) makes “Oppy” feel like he doesn’t have a place in society. At that moment, he begins to realize he is being pushed out and eventually rejected by those that once worshiped him. It is an emotionally devastating turn of events that Cillian Murphy plays beautifully. That conveyed pain makes the film's literal ending even more emotionally satisfying.

No matter how hard his friends and wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), fight for him, he does not win against the board. Kitty’s speech against the board helps his case but does not help him keep his clearance. At this point, it is revealed that Lewis Strauss (Downey Jr.) has been pulling the strings all along to discredit him.

“Oppy’s” affair with Jean Tatlock leads to his fall from grace until Strauss’s actions backfire. That is thanks to a former Met Lab technician (Rami Malek), who testified against Strauss. His testimony reveals Strauss’s personal grievances against Oppenheimer, recontextualizing all we have seen to this point.

Once Strauss’s true intentions are revealed, he loses his cabinet position in the Senate. It appears that both men have lost it all. It was not until 1963 that Oppenheimer was finally acknowledged by the government. President Lyndon Johnson bestows him the Enrico Fermi award, which is the highest honor the AEC can grant.

Oppenheimer is able to forgive those who testified against him, like Edward Teller (Benny Safdie). Whereas Kitty still held those grudges throughout the rest of her life. The film then gives one of the year’s most moving final moments.

Early in the film, Strauss attempts to introduce Oppenheimer to Albert Einstein. Oppenheimer reveals they already knew each other, and they go to speak in Strauss’s garden. Strauss, in his paranoid state, believes both men belittled him in conversation. Whereas in actuality, their discussion was something deeper and philosophical.

Both Oppenheimer and Einstein discussed the moral implications of what has been done and what could be done with the creation of this weapon. The power to destroy the world puts fear in both men about the future of nuclear warfare. A haunting closing image on Oppenheimer’s face lingers as he is in thought, and the screen cuts to black.