For over 50 years, the American Film Institute has worked to preserve and honor the heritage of American cinema; it has had an indelible effect in shaping the discourse around American film since its inception. As such, the AFI’s top lists are both a broad view of classic American films and a telling peek into what the creatives who curate the lists think a “classic” truly is.

So, what makes a horror classic in the eyes of the AFI? The films chosen are from a mélange of subgenres — suspense, monster movies, sci-fi, etc. — but they all do something to make audiences squirm. Some of the movies only started with cult audiences, while others were praised from day one, but what is most clear about all the films on the AFI’s top horror list is that these “bests” are created through a combination of high and low. On their own, the aesthetics might be over the top or the drama may be overwrought, but together, prestige and camp make for one interesting duo.

Before we dive in, two quick notes. The AFI’s list broadly combines thrillers with horror movies rather than specifically the latter, so for this list we’ve omitted thriller films that are decidedly not horror such as North By Northwest and The French Connection. Second: this list, though comprehensive in the sense of traditional film criticism, fails to explore beyond a canon of films and filmmakers that are overwhelmingly white and male. These are all incredible films that shaped the horror genre into what it is today, but the “best” is, of course, subjective, and always worth interrogating.

11 The Night of the Hunter

Directed by acclaimed actor Charles Laughton, The Night of the Hunter wasn’t beloved when it premiered in 1955. So much so, in fact, that this first-time director never directed again. But history has looked reverently back on this film, recognizing it as a masterpiece.

The Night of the Hunter follows the misogynistic serial killer and self-proclaimed preacher Henry Powell. Arrested for driving a stolen vehicle, Powell ends up sharing a cell with Ben Harper, a bank robber with $10000 and two dead bodies on his conscience. Harper reveals that only his two children know where he’s hidden the money before he’s hanged for his crimes. When Powell is released from prison, he weasels his way into the Harper’s widow’s life so that he can steal the money and maybe swindle a bit more along the way.

Laughton approached the film with an eye toward the past, to “restore the power of silent film to talkies.” What results is a moody, atmospheric piece that almost transcends genre entirely. That said, Laughton uses the power of silent film language like that in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligariand Nosferatu to terrify and inspire, and as such, has become an integral piece of the fabric of American horror cinema.

10 The Shining

For people of a certain age, The Shining felt like the pinnacle of horror cinema during childhood. The iconic imagery of the film — the bloodied Grady twins, the gushing blood from the elevator, “REDRUM” in Danny’s childish scrawl, etc. — all stood out as the most frightening things we could’ve seen at a sleepover. Upon seeing The Shining as an adult, the film is only made more horrific by the context in which those images are found.

Short on work and opportunity, recovering alcoholic Jack Torrance and his family move to the Overlook Hotel for the winter as live-in caretakers in the off season. But isolation doesn’t take long to push Jack beyond his limits, and the supernatural guests in the Hotel don’t help, either. The isolation and anguish that the Torrance family experiences are deeply disturbing, and the supernatural moments of horror serve to punctuate their dramatic weight. Yet again, this film demonstrates a provocative mixture of high and low to produce a thoughtful and engaging reflection on trying, and sometimes failing, to overcome our demons.

9 Deliverance

Deliverance is the classic horror tale of city-dwelling outsiders encroaching into a rural space where they aren’t welcome. It’s a theme that can be found in countless horror films like The Hills Have Eyes, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Wrong Turn: you don’t know what’s out there, and it’s dangerous to try figuring it out.

In Deliverance, four male friends embark on a trip to a remote river in Appalachia. They soon meet the locals, who aren’t particularly open to these outsiders. The men begin their canoeing, only to discover that they must fight through man and nature to survive the trip. It’s a harrowing film that reflects on man’s fruitless and destructive attempts to harness nature, pulling from literary traditions like the Southern Gothic and atmospheric films like The Night of the Hunter.

8 King Kong

Another example of a film where nature fights back, King Kong starts as an adventure story that quickly turns horrific. Filmmaker Carl Denham leads an expedition to a strange island where he hopes to shoot a film, only to discover the giant ape known as Kong. The ape falls in love with Ann Darrow, a young woman on the trip, and Denham and crew use this to their advantage to capture Kong. They bring the beast back to display him in New York City, but things quickly go awry when Kong escapes and begins wreaking havoc.

King Kong was a visual effects spectacle in 1933, something audiences had never witnessed before. While splashy VFX are practically an industry standard now, Kong was a sight to behold. This is thanks to pioneer Willis O’Brien, who came up with the idea to use stop-motion models and live actors in tandem, a technique that would shape film effects up to this very day. Creators inspired by King Kong include cinema legends like Ray Harryhausen, Steven Spielberg, and James Cameron, among countless others.

7 Rosemary’s Baby

Today, Roman Polanski’s filmography is often overshadowed by his criminal activity as well as the famous death of his wife Sharon Tate at the hands of the Manson Family cult. But before all of this, Polanski would cement himself in the landscape of American cinema with the 1968 adaptation of Ira Levin’s novel, Rosemary’s Baby.

Rosemary and her new husband Guy are newlyweds who’ve just moved into their New York City apartment. In short time, Rosemary gets pregnant, but her happiness is cut short when she begins to suspect that something suspicious and sinister is afoot in her building. Rosemary grows increasingly paranoid, wondering if her husband and neighbors are truly the members of a satanic cult out to get her and her unborn child, or if it’s all in her head.

Rosemary’s Baby is yet another example of combining B-movie concepts with prestige aesthetics. It was actually the B-movie king himself, William Castle, who purchased the rights to Levin’s novel and brought them to Paramount’s Robert Evans, so the combination makes complete sense in this case. In bringing together these two sensibilities, Rosemary’s Baby is equally exciting and thoughtful, reflecting on themes of gaslighting and the female autonomy.

6 The Birds

Psycho inspired filmmakers to take the titillation farther. From this arose creatives like Herschell Gordon Lewis, the “Godfather of Gore” and creator of such films as Blood Feast and 2000 Maniacs. For Hitchcock’s next horror film, he would take inspiration from imitators like Lewis. The Birds is an environmental catastrophe movie that filters the titillating films it’s inspired by through Hitchcock’s uniquely terrifying style and biting wit.

The Birds follows socialite Melanie Daniels as she attempts to track down and woo Mitch Brenner, a man she just met in a pet store. Soon after she arrives in Brenner’s town of Bodega Bay, Melanie notices the local birds behaving strangely. The creatures’ behavior grows increasingly violent and erratic, and Melanie and the rest of the townspeople must find away to escape their onslaught.

The film is perhaps the clearest example of where Hitchcock often locates the horror in his films, that is in aesthetic excess. Similar to the famous Psycho shower scene, the scares in The Birds are built up with subtle tension to the point of breaking, at which point the viewer is inundated with the birds’ obnoxious screeching and the editing’s quick, violent cuts that make us truly feel terror.

5 Alien

In the '50s and '60s, aliens in the movies were either thinly veiled communist invaders or giant bugs. In 1979, Alien introduced audiences to a new kind of extraterrestrial. A far cry from the monsters before it, the Xenomorph embodies a terror that is at once familiar and yet utterly unknowable. It isn’t a man in a silver suit or an enormous ant, it’s a miasma of recognizable features — a beetle’s exoskeleton, a scorpion’s tale, an eel’s jaw, etc.—mashed together into one terrifying creature.

What truly sets Alien apart from the science fiction that came before it, though, is its skillful combination of high and low: it’s a B-movie plot with a prestige aesthetic. In fact, before Ridley Scott was attached to direct, the project almost went to B-movie king Roger Corman. Alien is, as Gene Siskel put it, a “haunted house movie in space,” and that’s precisely what makes the movie so fun and fascinating.

4 The Silence of the Lambs

Unlike something like Psycho, which had to grow on audiences before gaining its “classic” status, Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs was immediately recognized by critics and audiences. That year, it won every category of the “Big Five” Academy Awards — Best Actor, Actress, Screenplay, Director, and Picture. To this day, it is still one of only three films to do so.

The Silence of the Lambs was the prestige horror of its day, “elevated” to the genre of thriller by critics to indicate its apparent superiority. But make no mistake, this movie is horror through and through; it’s a police procedural drenched in gothic ambiance, psychological terror, and gut-wrenching gore. The Silence of the Lambs transformed the serial killer from a raving madman to a cold, calculating monster.

3 The Exorcist

Often considered one of the scariest films ever made, The Exorcist is a testament to the influence of film on the public consciousness. As a practice, exorcisms were on the decline before William Friedkin’s 1973 film premiered, but the Catholic Church experienced a windfall of exorcism requests from a public eager to place the blame of mental and social ills on the abstract shoulders of a demon like Pazuzu. The Church, with its own demons to hide, was glad for the laundering of their reputation the film provides, even if they didn’t know it at the time.

The Exorcist scared a generation into believing that demons lurk around every corner; its influence on culture can’t be understated. Its influence on film, though, is even more momentous, as it re-legitimized the horror genre for a new generation. This is a movie that is smart and exciting in equal measure, exploring not only the intricacies of faith, but those of motherhood and adolescence. The Exorcist may not scare you in this day and age, half a century after its production, but it’s hard not to appreciate everything the film does right.

2 Jaws

When the mechanical sharks on the set of Jaws kept failing, Steven Spielberg turned to Hitchcock’s approach: the power of the scares would be in the suggestion of a monster. We tend to fear the things we can’t see or understand, and that’s precisely what Spielberg capitalized on when making Jaws. Considered the first summer blockbuster, Jaws follows the tourist town of Amity Island as it is menaced by a man-eating great white shark.

Jaws has thrills and scares in equal measure, but in recent years its commentary on the invariable thrust of capital, even in times of great duress, is felt far more plainly. Spielberg’s blockbuster expertly explores themes of man vs nature, specifically man’s arrogant attempts to manage the natural world according to his own narrow desires. The beach must remain open, not because it’s safe to go there but because it’s tourist season, and money is on the line. It’s a sentiment many of us have now experienced first-hand. Jaws feels unnervingly prescient in a post-Covid world, demonstrating the power film can have to speak beyond its creator’s intentions and exactly why it deserves to be so high on this list.

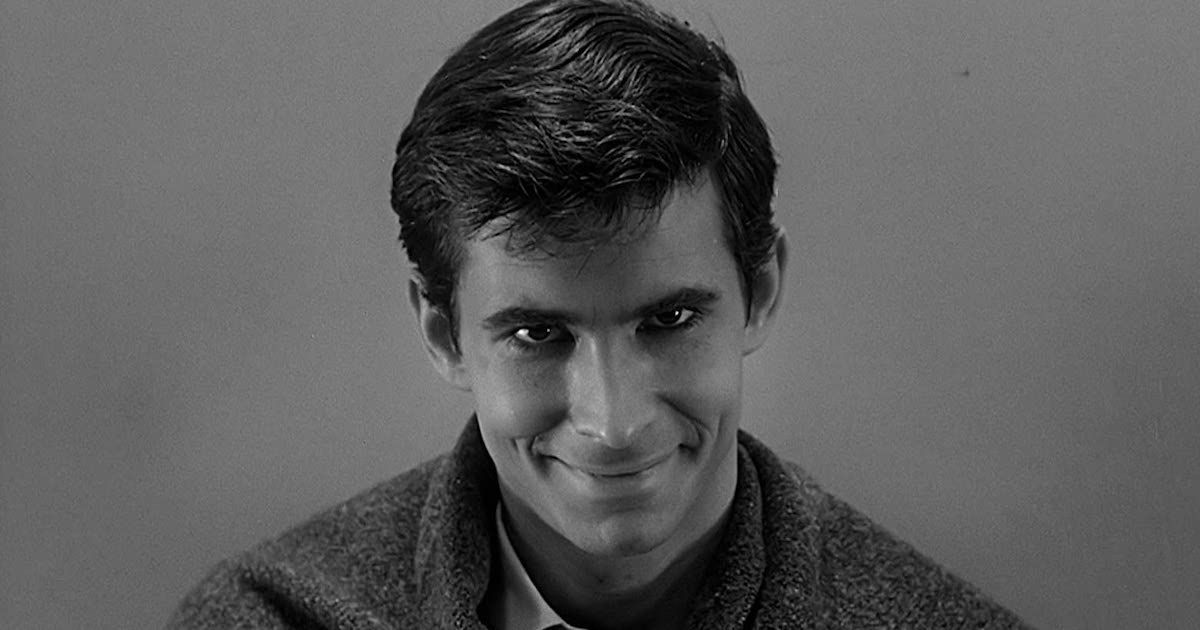

1 Psycho

It’s no surprise that Psycho is in the number one spot on the AFI’s list. Based on the novel of the same name by Robert Bloc, this psychological nightmare is still unsettling despite premiering over 60 years ago. Psycho represents a huge shift in not just Alfred Hitchcock’s style, but in the horror genre as a whole; the film established many techniques and ideas that we still see in genre films to this day.

Before Psycho, Hitchcock’s filmography leaned further into thrillers and suspense and less into grisly, uncanny horror. Similarly, horror film in general was quite different in the years preceding Psycho. Monster movies had reigned supreme for decades, but Psycho switched things up by having the monster be a man rather than a rubber-suited creature. Creature, no, but beast, yes: Norman Bates establishes the slasher killer archetype, stalking his prey and pouncing when the moment is right. Without Norman and his famous mommy-issues, we wouldn’t have some of our favorite horror villains like Jason Voorhees and Freddy Krueger.

.jpg)